Giant Steps and Metastasis

A Journey Through Coltrane, Xenakis, and the Philosophies of Flow and Form

Last week, I was deeply moved by Brad Mehldau's extraordinary album, "Après Fauré," which pays a heartfelt tribute to the remarkable French composer Gabriel Fauré. What resonated with me was Mehldau's ability to combine meticulous structure with a rich emotional depth—crafting music that captivates both the analytical mind and the intuitive heart. This experience reminded me of a journey I once embarked on through the intricate layers of Steve Reich's minimalism and the haunting melodies of Jonny Greenwood's score for "There Will Be Blood." Both compositions navigate the delicate balance between mathematical precision and profound emotional depth.

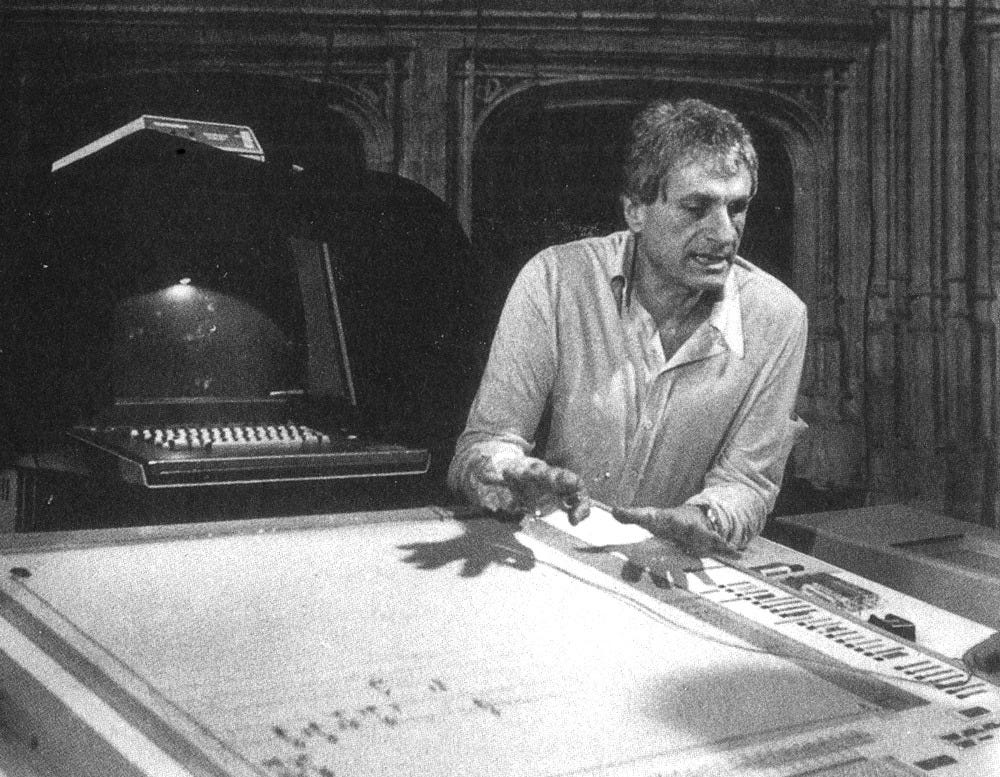

Years ago, during my journey into the realm of generative music, I stumbled upon Iannis Xenakis, an extraordinary Greek-French composer and architect. His unique mathematical approach to composition not only fascinated me but also revolutionized the landscape of modern classical music. In "Iannis Xenakis: Composer, Architect, Visionary," I found it interesting to discover how he employed architectural drawing techniques in his composition process. His works, rooted in mathematics, manage to transcend their origins, mixing profound internal reactions that linger long after the music fades. What intrigued me about his piece "Metastasis" was its ability to embody both the rigor of mathematical precision and the richness of sensory experience all at once.

This journey unfolded alongside my investigation into entropy, as detailed in my earlier article. (see below)

This thread led me to Henri Bergson, a French philosopher whose ideas I had not previously studied. Curious about his ideas, I stumbled upon a thought-provoking essay penned by Bertrand Russell, the famous British philosopher and mathematician. It struck me that Russell, even with his opposing viewpoints to Bergson's, devoted considerable effort to exploring and interacting with Bergson's concepts. I wondered if analytical precision and intuitive understanding are incompatible. Or could they be complementary in some way?

Because of these questions, I thought about John Coltrane. His groundbreaking piece "Giant Steps" seemed to capture this tension perfectly. I wondered how Coltrane's mathematical harmony could produce such fluid and spontaneous music. Could the structure enable, rather than constrain, the intuitive flow of improvisation?

The dynamic relationship between rationality and intuition, as well as structure and flow, has always intrigued human thought. It makes me think of Hermann Hesse's beautiful book "Narcissus and Goldmund," which has two characters with very different ways of living: one is devoted to the contemplative life of the mind, and the other is an artist and craftsman who enjoys direct sensory experience. Their journeys suggest that these approaches may not be as distinct as they appear, eventually revealing complementary paths to understanding rather than opposing ones.

This integration of seemingly opposing modes of understanding occurs not only in modern literature, but also in ancient thought. Peter Kingsley's exploration in "Reality" fascinates me, as he delves into the ancient poems of Parmenides with a fresh perspective. Although Parmenides is often linked to the rational tradition, Kingsley presents a compelling argument that "logos" (commonly translated as "reason") had a fundamentally different connotation—one that intertwined logical analysis with intuitive insight, creating a more integrated understanding of knowledge. Hesse's novel and Kingsley's historical analysis reveal a lost unity that existed before today's split between rational and intuitive thinking.

I started to question whether there might be more profound connections between these seemingly unrelated themes as I thought about Coltrane, Xenakis, Russell, and Bergson. Could something about how we perceive reality, structure, and flow be revealed by analyzing Xenakis's "Metastasis" and Coltrane's "Giant Steps" against the philosophical backdrop of Russell and Bergson's opposing worldviews? This substack represents my attempt to investigate these connections and the implications for the relationship between seemingly opposing modes of understanding.

Two Groundbreaking Perspectives on Musical Time

It's 1959. In a New York recording studio, John Coltrane's saxophone dances through the demanding chord changes of "Giant Steps," his fingers flying across the instrument as he navigates the composition's complex harmonic maze with seemingly impossible fluidity. Across the Atlantic, just four years ago, the premiere of Iannis Xenakis's "Metastasis" presented orchestral players with densely notated mathematical structures, glissandi moving in precisely calculated trajectories, and sound masses that appear to exist outside of conventional musical time.

These two groundbreaking compositions, born almost at the same time yet rooted in vastly different musical traditions, embody unique methods of musical creation that reflect a deep philosophical divide: Bertrand Russell's analytical precision, on the other hand, carefully separates reality into its logical parts. Henri Bergson's idea of intuitive length, on the other hand, sees time as a continuous flow of experience. However, a closer examination reveals that neither component truly aligns with the extreme opposites.

Both compositions exist in an intriguing middle ground where rigorous structure and intuitive flow not only coexist, but also rely on one another.

This tension between analytical framework and experiential flow reveals a more profound truth about human creativity and consciousness. Examining these musical works against the philosophical backdrop of Russell and Bergson's contrasting worldviews may reveal that the most profound artistic achievements transcend such dichotomies, implying a complementary relationship between seemingly opposing modes of understanding.

The Russellian Architecture: A Journey from Giant Steps to Metastasis

At first glance, Coltrane's "Giant Steps" appears to exemplify jazz's improvisational freedom, whereas Xenakis' "Metastasis" represents the pinnacle of calculated composition. However, both works are supported by sophisticated mathematical structures that would have appealed to Russell's analytical mind.

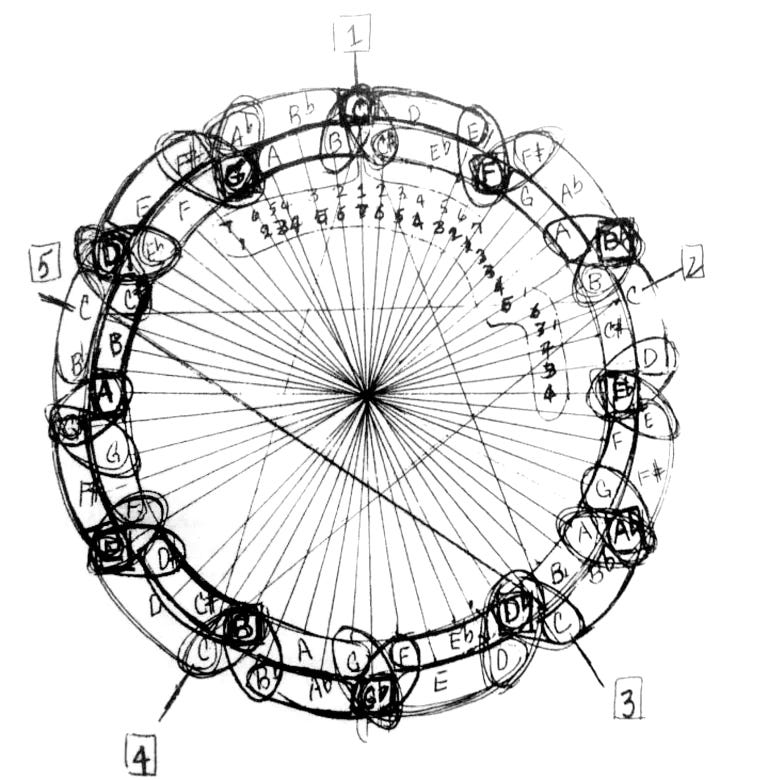

Coltrane's composition is based on what musicians now refer to as the "Coltrane cycle"—a symmetrical division of the octave into three equal parts, resulting in a progression through three key centers separated by major thirds. This mathematical precision results in a harmonic framework that, at the time of its creation, was considered nearly unplayable due to its rapid modulations. (Check out the excellent mini-documentary about Giant Steps and the Coltrane changes.)

The chord changes in "Giant Steps" provide a logical solution to a musical problem: how to connect distant tonal centers while maintaining harmonic motion. Coltrane approached the challenge methodically, practicing patterns and permutations for years before recording the piece.

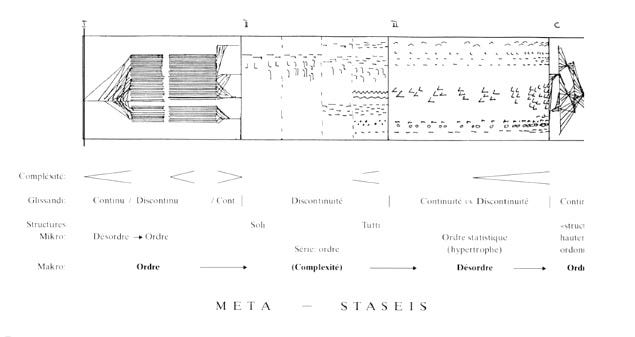

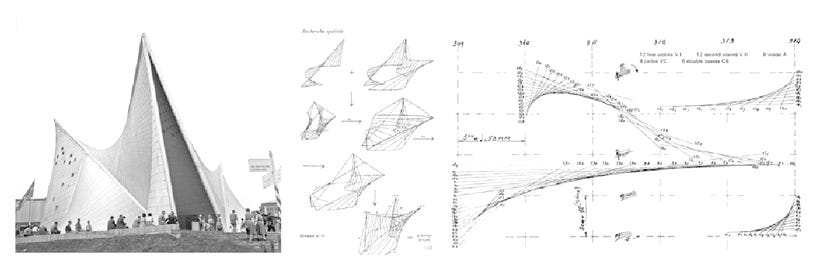

In a striking parallel, Xenakis, drawing from his roots in engineering and architecture, tackled composition as if it were a complex mathematical problem. "Metastasis" grew out of his collaboration with Le Corbusier and his fascination with architectural principles applied to music. Xenakis used stochastic processes, probability theory, and set theory to determine pitch, duration, and density. The famous glissandi sections of "Metastasis" were based on the same mathematical principles used to design the Philips Pavilion for the 1958 World Exhibition in Brussels—hyperbolic paraboloids that created surfaces from straight lines.

Xenakis himself captures the essence of sound in a way that feels both personal and profound: "The collision of hail or rain with hard surfaces, or the song of cicadas in a summer field. These sonic events are made out of thousands of isolated sounds; this multitude of sounds, seen as a totality, is a new sonic event." His method of composing through the mathematical formalization of nature aligns strikingly with Russell's conviction that mathematical logic can articulate reality with greater precision than mere intuition. This intersection of sound and mathematics invites us to reconsider how we perceive the world around us.

Even with their mathematical foundations, both pieces resonate as lived sound, guiding us into the realm of Bergson.

Bergson's Duration: The Surprising Current Beneath the Surface

While the architectural elements of both compositions are consistent with Russell's analytical approach, the actual musical experience—for both performers and listeners—is of Bergsonian duration.

For Coltrane, even within the strict confines of "Giant Steps," the essence of improvisation lies in transcending analytical thought, allowing the musician to immerse themselves in a state of subconscious creativity. Musicians who have taken on "Giant Steps" describe a profound journey, one that begins with the hard analytical struggle and evolves into a state of intuitive mastery. It's a transformative experience where the intricate mathematical patterns are absorbed so deeply that the performer moves beyond the realm of conscious calculation, entering a space of pure expression. McCoy Tyner, the pianist who would later become part of Coltrane's quartet, stated, "When you're truly improvising, it's not about thought; it's about feeling."

This experience resonates deeply with Bergson's idea of duration, illustrating how time is not merely a series of isolated moments but rather a seamless continuum, where the past, present, and future intricately blend into one another.

In improvisation, each note played immediately becomes a part of the past, shaping the current moment and the solo's future direction. The musician exists in a state of constant becoming that cannot be fully captured by analyzing individual notes or measurements.

Unexpectedly, Xenakis's meticulously structured "Metastasis" evokes an experience that deeply connects with the essence of Bergsonian duration. The sweeping glissandi evoke a sense of ongoing transformation in sound, compelling listeners to engage with music as a fluid journey rather than a collection of static notes. The title "Metastasis," which translates to "beyond stasis," reveals Xenakis's deep fascination with transformation and the dynamic process of becoming, instead of a mere existence in a static state.

Xenakis, with his mathematical lens, still held a profound respect for the elusive nature of intuition in the art of composition. He articulated, "There is a formalization of music with the aid of mathematics, but there is also an intuition that escapes this formalization and which is indispensable for the development of human thought." This recognition of intuition's vital contribution resonates deeply with Bergson's belief that the essence of reality can only be truly understood through intuition, not mere analysis.

The performers of "Metastasis," even while adhering to meticulously notated instructions, find themselves immersed in the music's unfolding, resonating with a sense of Bergsonian duration. One orchestra member who performed the piece reflected, "The individual notes vanish into something greater—you're crafting a sound mass that unfolds in time in a way that defies traditional music."

The Meeting of Contrasts in Musical Traditions

What makes the comparison of Coltrane and Xenakis especially interesting is how each composer's trajectory shows a shift away from their starting points and toward the integration of opposing principles.

Following "Giant Steps," Coltrane began to delve deeper into a realm of freer, more instinctive compositions. Albums such as "A Love Supreme," followed by "Ascension" and "Interstellar Space," reveal his gradual departure from rigid mathematical confines, embracing a more spiritual and intuitive form of expression. However, this freedom was only possible because he had mastered the most rigorous structures. He traversed a path from the analytical rigor of Russell to the fluidity of Bergson's intuition, yet it was the clarity of the former that paved the way for the latter's insights.

Xenakis, while steadfast in his mathematical foundations, gradually embraced the profound emotional and experiential dimensions of his music. "Metastasis" might have been crafted through formulas, yet it evokes a profoundly visceral and emotional journey. As Xenakis' career progressed, works such as "Jonchaies" and "Pleiades" retained mathematical rigor while becoming more sensually engaging. His journey balanced meticulous clarity with a deep understanding of the listener's lived experience.

Musicians interpreting the compositions of both composers often share strikingly similar experiences, even though they hail from distinct traditions.

Jazz musicians often describe the experience of "getting beyond the changes" in Coltrane's music, seeking a state of flow that transcends mere notes. Similarly, classical performers interpreting Xenakis discuss the challenge of discovering "the music beyond the math." Both paths demand a departure from analytical constraints to achieve a deeper, intuitive grasp of the art. However, this transcendence is only attainable after a thorough mastery of the underlying structure.

This convergence suggests that Russell and Bergson's approaches may be complementary, addressing different aspects of the same reality. Just as light embodies the duality of particle and wave, human creativity and consciousness might also demand a delicate balance between analytical precision and intuitive flow.

Expanding Beyond Simple Contradictions

The musical examples of Coltrane and Xenakis compel us to rethink the Russell-Bergson contrast, urging us to see it not as a rigid choice but as a rich spectrum where various modes of understanding can harmoniously coexist.

Russell's focus on logical analysis offered essential tools for sharpening concepts and steering clear of the ambiguity that often clouds intuitive methods. Even Russell himself recognized in his later writings that relying solely on logical analysis falls short of capturing the entirety of human experience or the imaginative leaps that fuel both artistic and scientific breakthroughs.

Bergson's focus on intuition and duration reveals a profound truth about the essence of lived experience, one that defies the confines of analytical reduction. Without an analytical framework, those intuitive insights linger in isolation, locked away from communication and challenging to expand upon.

Both "Giant Steps" and "Metastasis" show how the most profound creative achievements combine both modes of understanding. The analytical offers a framework that enhances clarity and understanding, while the intuitive infuses life with essential energy and a deep connection to our personal experiences.

This integration mirrors the advancements seen in various other domains. Quantum physics has unveiled the necessity for analytical models to embrace uncertainty and the influence of the observer—ideas that might resonate more with Bergson's philosophical musings than with the rigid frameworks of Russell.

Cognitive science increasingly recognizes that human thinking involves both rule-based processing and intuitive pattern recognition, which work together rather than against each other.

It seems that the philosophical legacy of these musical compositions hints at a possibility: the chasm between analytical and Continental philosophical traditions, frequently depicted as unbridgeable, might actually be more traversable than the intricate harmonic landscape of "Giant Steps" or the dense soundscapes of "Metastasis."

Evolving from Human to Computational Creativity

Artificial intelligence and computational creativity have added a new dimension to this philosophical exploration. Efforts to program computers for improvisation on "Giant Steps" or to create compositions reminiscent of Xenakis expose the distinct challenges associated with these methods.

Imagine AI systems delving into the depths of Coltrane's improvisations, crafting fresh solos that dance over the intricate "Giant Steps" changes. The fusion of technology and artistry opens a vivid realm of possibilities, challenging our perceptions of creativity and musical expression. These systems possess the remarkable ability to dissect patterns and replicate stylistic nuances with an ever-growing level of sophistication. Musicians often express a deep-seated frustration with computer-generated improvisations, noting a stark absence of the unique quality that makes human improvisation so captivating. This essence, reminiscent of Bergson's concept of élan vital, embodies a creative impulse that defies reduction to mere algorithms.

Xenakis's stochastic methods are particularly suited for computational implementation, showcasing a remarkable synergy between his innovative approach and modern technology. In the 1970s, he introduced the UPIC system, a pioneering venture into the realm of computer-aided composition. Even in this realm, the human touch is indispensable, guiding the establishment of parameters, assessing outcomes, and making those instinctive leaps that mere computation simply cannot replicate.

The journey through these technological explorations reveals a profound truth: although we can mimic analytical precision and creative flow to an extent, the true magic lies in their integration. Coltrane and Xenakis' music, with its intricate dance between structure and freedom, embodies a unique human magic. This implies that the dichotomy between Russell and Bergson, instead of being settled in favor of one perspective over the other, might be transcended by their synthesis within the realm of human consciousness.

Final Thoughts

"Giant Steps" and "Metastasis," born from distinct traditions and crafted by composers with unique backgrounds, unveil a shared truth: the most significant artistic accomplishments rise above the divide between analytical structure and intuitive flow, showcasing their inherent interdependence.

While Xenakis's strict formalism crafts experiences that unfold in a Bergsonian sense of time, Coltrane's meticulous mathematical structure allows for his boundless improvisation. Both works challenge us to move beyond seeing Russell's and Bergson's approaches as diametrically opposed, arguing that they address different aspects of a single reality.

For performers, achieving mastery demands a blend of analytical insight and instinctive flow—the capacity to fully embrace structure, allowing true freedom to emerge from within it. For listeners, this means that our experience with these works engages both our analytical and intuitive understanding of duration.

The philosophical implication is that human consciousness may function at this intersection, combining analytical precision and intuitive flow in ways that cannot be reduced to either. Time, in our lives, is not just a cold calculation or a mere feeling; it is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of quantifiable moments and the deep, personal experiences that shape our understanding of existence.

When we listen to Coltrane navigate the demanding changes of "Giant Steps" or experience the massive sound transformations of Xenakis' "Metastasis," we are not choosing between Russell and Bergson; rather, we are experiencing the integration of their insights. These musical works, each in their unique manner, reveal that true understanding emerges not from a stark choice between analytical precision and intuitive flow, but from their vibrant interplay within the ever-evolving tapestry of human experience.

This integration may lead to not only a greater appreciation for these revolutionary musical works, but also a more comprehensive philosophical approach to consciousness, creativity, and our experience of time itself—one that recognizes both the precision of the mathematician and the flow of the improviser as essential, complementary aspects of what it means to be human.

About the cast:

John Coltrane (1926-1967) - An influential American jazz saxophonist and composer who revolutionized jazz through his innovative harmonic approaches and spiritual explorations. His album "Giant Steps" (1960) is considered a masterpiece that pushed the boundaries of jazz improvisation through its complex chord progressions and rapid key changes.

Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) - A Greek-French composer, music theorist, and architect who pioneered the use of mathematical models in music. Having survived facial injuries as a resistance fighter in WWII, he later studied engineering before working with the architect Le Corbusier and developing his unique approach to composition using stochastic processes and game theory.

Henri Bergson (1859-1941) - A French philosopher who developed the concept of "duration" (durée) as lived time that cannot be divided into discrete moments but is experienced as a continuous flow. His work on time, consciousness, and creative evolution challenged mechanistic views of reality, emphasizing intuition as a way of understanding life's deeper nature.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) - British philosopher, logician, and mathematician who helped establish analytic philosophy. He advocated for logical precision and mathematical rigor in philosophical thinking, attempting to ground knowledge in logical foundations. His work with Alfred North Whitehead on "Principia Mathematica" exemplified his analytical approach.